We've never had so much content at our fingertips: 24/7 channels, nearly unlimited on-demand catalogs… and yet, choosing what to watch has become exhausting. The overabundance leads to decision fatigue for viewers. This phenomenon is especially evident in the FAST/AVOD ecosystem, where growth has been remarkable in recent years. This rapid expansion has created a complex landscape for both platforms and audiences, who now face the challenge of finding value and differentiation in a sea of channels.

In this article, we'll explore the evolution of the FAST ecosystem over the past decade, with a particular focus on the growing number of available channels. Many of the insights we’ll share could also apply to the broader AVOD universe—especially considering that, in many cases, the same content exists in both environments: broadcast linearly through FAST channels while also being available on demand.

The difference between FAST (Free Ad-Supported Streaming Television) and AVOD (Advertising Video On Demand) lies not so much in what is offered, but in how the viewing experience is structured:

In practice, both models often coexist within the same platform and share content. But while AVOD follows a logic of individual control—where the viewer decides what to watch and when—FAST offers a more passive experience, centered on discovery and background viewing

Both share a common foundation: they are free and monetized through advertising.

Among FAST channels, we can identify several operational and distribution models:

In this context, where a channel is distributed is just as important as the content it offers. Being part of a saturated environment—with hundreds of channels competing for visibility—is not the same as being featured in a more curated, editorialized setting with a limited and carefully selected offering.

Both the number of FAST channels and their audiences have grown exponentially in recent years.

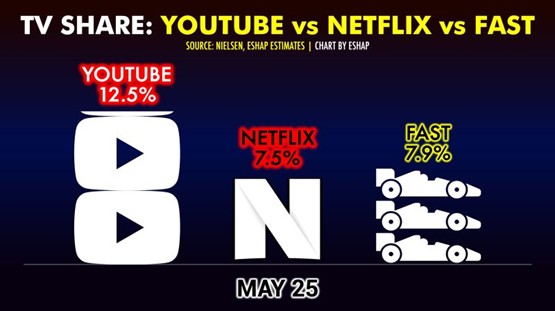

To get a sense of FAST's scale, the combined viewership share of FAST channels in the U.S. in May 2025 surpassed that of a giant like Netflix (source: Evan Shapīro).

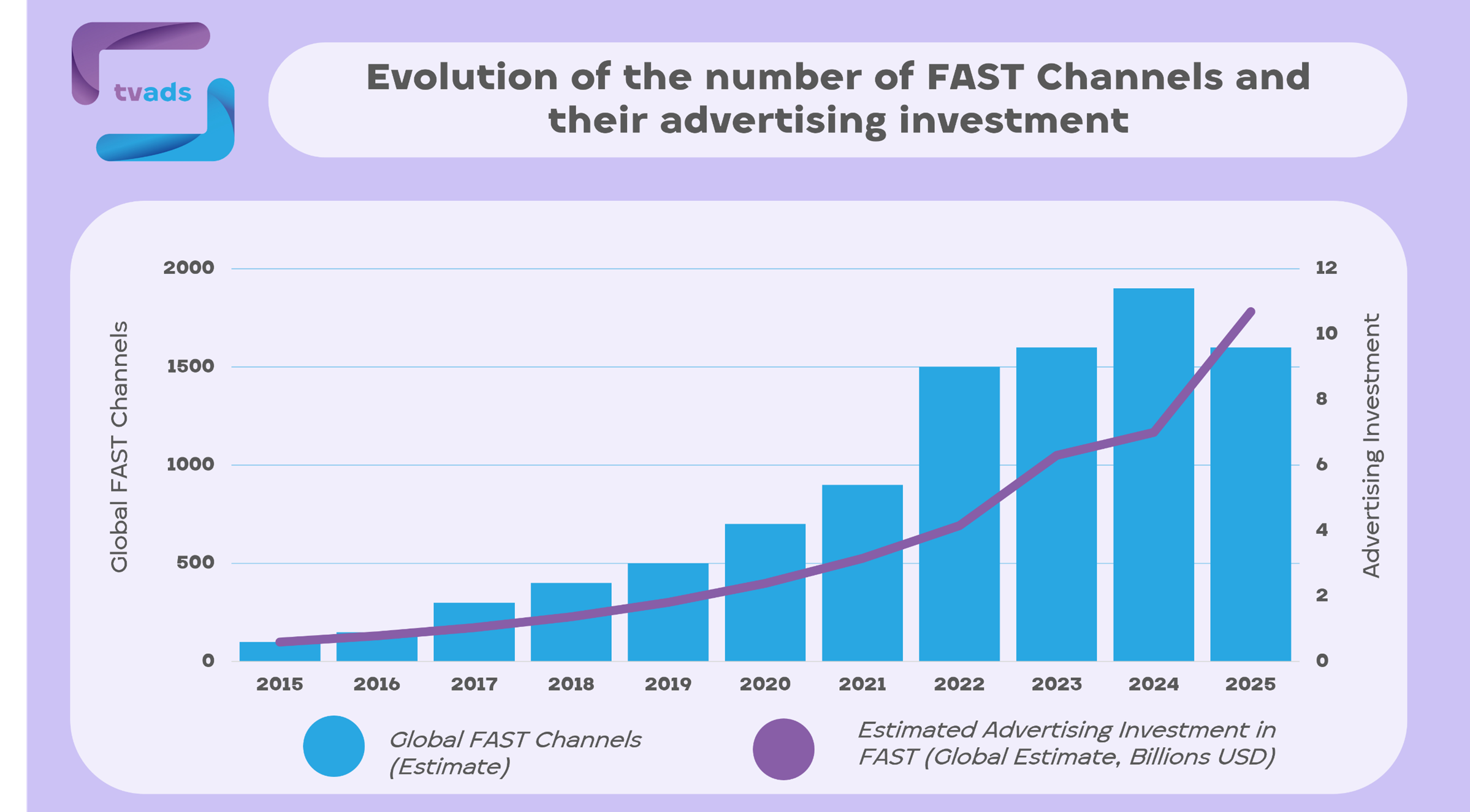

Since its emergence around 2015, when there were barely 100 channels worldwide, the ecosystem has experienced remarkable growth. Until 2021, the increase was gradual, reaching 900 channels. From that point on, the pace accelerated and expanded into other markets. In May 2024, a peak of 1,943 unique channels was reached (according to Broadcast Intelligence), but since then the number has begun to decline, standing at around 1,610 channels as of March 2025. This suggests a new phase of pruning and consolidation following the period of massive expansion.

This growth, however, has brought with it extreme fragmentation. Channels dedicated to a single series, very specific subgenres, or highly niche topics like “gluten-free cooking” or “80s thrillers” have proliferated. For a time, this phenomenon was celebrated as a sign of success: the more channels, the better. But as the model matures, a new key question arises: does it make sense to keep adding channels without a clear strategic purpose? Which leads us to the next question: is the number of channels growing at the same pace as their actual monetization potential?

The following chart shows the evolution in the number of FAST channels from 2015 to 2025. This overview allows us to visualize the general growth trend up to 2024 (as mentioned above) and compare it with the evolution of advertising revenues associated with this model.

At first glance, the relationship between supply and monetization is not linear. The sharp increase in channels between 2021 and 2022 (when the number of channels nearly doubled) was accompanied by advertising growth, but not in equivalent proportion. Since then, and up to 2024, the volume of channels has remained high, but investment has not kept pace.

In 2025, the outlook has become more uncertain. Some projections, such as TVREV and Omdia, anticipated very significant growth in global advertising investment. However, other sources, like a recent analysis in The Information , report testimonies from platforms claiming to be experiencing 50% drops in revenue on some of their channels.

Although this may seem somewhat contradictory at first, both statements likely contain some truth. While the most optimistic forecasts from firms like TVREV and Omdia may have overestimated the growth pace, advertising investment in FAST continues to rise. However, growing investment doesn’t mean that growth benefits all players in the ecosystem. The current extreme fragmentation is also causing an uneven distribution of revenue: while some well-programmed channels with differentiated content are growing exponentially, others (less relevant or offering generic content) are seeing their profitability decline significantly.

In a market as saturated as today’s, sustainability no longer depends on the number of channels but on their ability to attract audiences and advertising investment through a solid, well-curated offering with a clear differentiation strategy.

Everything points to the FAST ecosystem entering a new phase: less focused on volume and more on efficiency, quality, and profitability.

Several reasons explain this growth, the main ones being:

Both proved that success in FAST depends not just on “having content,” but on how it is organized, grouped, presented, and made discoverable. This early success has inspired many to imitate the model… though not all have managed to replicate it with the same effectiveness.

Below we outline a series of reasons that could explain the slowdown or the lack of growth as previously anticipated:

Although audiences continue to grow, investment is not keeping pace. This gap highlights that the challenge is no longer scaling volume but consolidating a profitable and sustainable model.

A channel without an audience doesn’t generate revenue. And capturing attention today is harder than ever.

Although thousands of channels are active, only a fraction manage to attract meaningful traffic. Most users don’t explore beyond the first visible channels. Without a clear editorial proposal or mechanisms to retain attention, many channels simply “do not exist” for the viewer.

This oversupply has created a paradox: more content does not mean more viewing, but more indecision. Many viewers end up browsing for minutes… without actually watching anything.

As we’ve seen throughout this article, this situation highlights the importance of having a clear and well-defined strategy when launching a FAST channel. It’s not just about choosing content, but about making conscious decisions regarding:

In a saturated ecosystem, curation, context, and visibility are just as important as the content itself.

Everything points to yes. The growth in the number of channels has outpaced consumption time and revenue generated. And some platforms have started to react.

Samsung TV Plus, Roku, and Pluto TV have already removed underperforming channels. This pruning is not just cosmetic: it aims to improve user experience, raise inventory quality, and free up space for better-thought-out offerings. The FAST ecosystem might be entering a correction phase, where content selection and differentiated value become key again.

The FAST model remains promising but needs to mature. Not all content deserves its own channel, nor does every channel find its audience. Oversupply, far from being an advantage, can turn into noise. The question should not be, “How many more channels can we launch?” but rather, “Which ones provide real value to users and advertisers?” And perhaps that is the key to FAST’s future: less, but better.

At tvads we has a professional team able to advise you on this field and and guide you in any area of your streaming advertising business, advising you or even operating it on your behalf if necessary

All author posts