Recently, two main questions have generated discussion among Industry players:

These debates stem from YouTube’s strong performance in recent quarters, particularly regarding its growth in the CTV environment.

These strong results are backed up financially:

As shown in the chart below, it is the streaming platform with the highest YoY growth.

Source: owl&co

But also when we look at content consumption within the platform itself.

In our previous article celebrating YouTube’s 20th anniversary, we already shared data on its global audience across all devices.

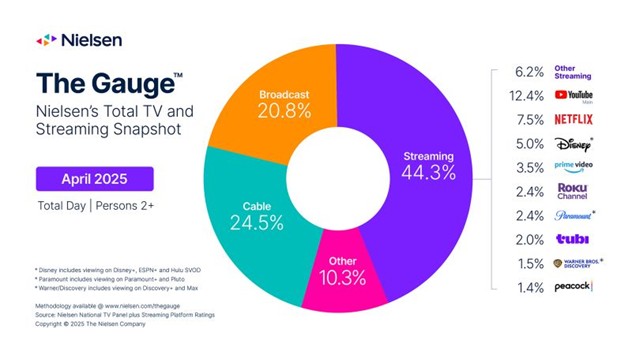

The latest reports from Nielsen Gauge and other measurement providers show that YouTube holds an audience share of over 12% in the U.S. and more than 10% in Europe within the CTV ecosystem.

Source: Nielsen

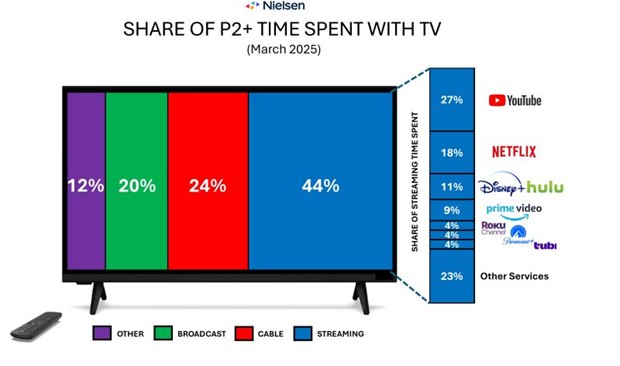

Out of the total streaming consumption on CTV, YouTube shows a clear trend—capturing between 25% and 30% of that share.

Source: Nielsen

In terms of overall audience figures—extending reach across all devices—the numbers are striking: 84% of internet users watch YouTube at least once a month.

In other words, the data confirms YouTube’s strong global performance and the solid position it holds within the CTV landscape—which, by 2025, is no longer all that new.

But returning to the debates we started with,

Without a doubt, it seems clear that the main party interested in this debate is Google itself.

Why? Because Google already controls a very large share of conventional digital advertising and now wants to do the same with traditional TV budgets. Media agencies have separate teams for buying digital advertising, outdoor advertising, TV advertising, etc.

Considering that growing digital advertising budgets is already challenging due to Google’s high market share, Google's move has targeted traditional TV teams directly in order to increase its share by tapping into budgets it hadn’t previously accessed.

Here, it’s worth mentioning an interesting fact. In 2024, YouTube generated $36.7 M USD in advertising revenue, compared to the $170 M USD brought in by the global TV industry. That’s a significant figure, and without a doubt, traditional broadcasters and TV media have good reason to be concerned.

There are several moves that clearly support the idea that it’s Google itself driving this debate.

Recently, it was reported that YouTube is trying to persuade voters and advertisers that its shows and platform stars should also be eligible for the Emmys.

Those who argue that YouTube is not TV, base their stance on the way users consume content on the platform. Ted Sarandos recently stated that YouTube is a place where users go to kill time. These comments need to be understood in context, Ted is fully aware that YouTube is currently Netflix’s biggest rival in the streaming wars.

Average viewing time: Historically, YouTube was a platform that users mostly accessed via mobile devices, with highly frequent but very short viewing sessions. This contrasts with traditional TV consumption, where viewers typically don’t engage in short bursts, but rather sit down to watch content for sessions lasting over 30 minutes. Undoubtedly, with the rise of YouTube consumption on other devices—particularly TVs (CTV)—this viewing model has changed.

The average time users spend watching YouTube on TV screens has increased significantly compared to the average time the platform used to register on mobile devices.

Historically, the predominant type of content on YouTube consisted of “non-professional” videos created by anonymous users who filmed and uploaded moments from their daily lives.

But truth be told, this has changed significantly in recent years. Content creators have become more professional, and many top creators now have their own recording studios and production teams.

And it’s not only niche audiovisual content producers on the platform who have raised the quality bar—more and more (and this ties into the second point of the debate) broadcasters and production companies that previously relied on other distribution channels are now turning to YouTube as a means of content distribution, driven by its massive audience potential.

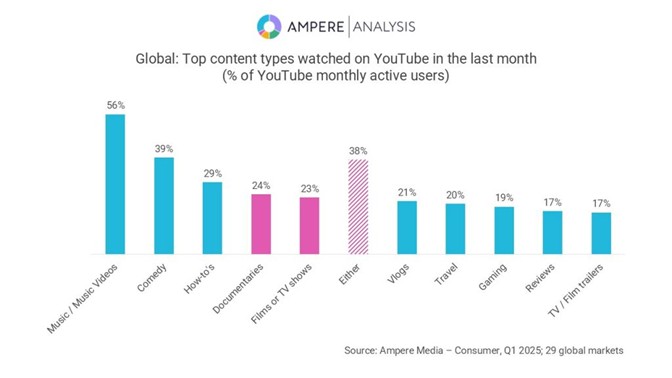

These changes are clearly reflected when we look at the types of content being consumed, where we can see a significant shift in trends.

According to a recent study by AMPERE:

Example Flow with Estimated Timings

Source: Ampere

And as a closing point to this debate, those who argue that YouTube is TV rely on one essential principle:

When a user watches any kind of content on the home TV screen, that’s TV. And while some may question this basic premise, in minds of users consuming YouTube via a TV device, they are watching TV.

As a starting point, it’s worth noting that when you listen to (or read) the arguments from both sides—those in favor of integrating with YouTube and those against it—both strategies sound equally convincing and reasonable.

Those in favor of encouraging broadcasters to integrate their content into the video platform base their argument on YouTube’s enormous audience potential. An undeniable reality is that traditional distribution models—like linear TV—have lost a significant share of both audience and viewing time, and that decline is far from over. Reaching younger audiences, who are no longer within the broadcasters' current distribution ecosystem but instead on other types of platforms, must be a top priority today.

And among those platforms, the biggest one is YouTube.

Another point made by advocates of integrating content into YouTube is that it offers additional revenue outside the broadcaster’s existing distribution channels. In other words, it’s as simple as adding new income to what you’ve already established. At this point, it’s worth remembering (as a general starting point, since there are specific details and exceptions) that YouTube operates on a revenue share model, allocating 55% of each income stream to content owners or licensors. As Evan Shapiro puts it: “This is NEW MONEY.”

On the other hand, those who oppose this kind of content integration strategy argue that it’s not really NEW MONEY—you’re actually sharing revenue with a third party that should rightfully be yours as a broadcaster. What’s more, you’re sharing it with a platform that is, directly or indirectly, your competitor. So, by offering your content there, you may end up helping your competition grow.

And this is where the disagreement resurfaces. Those who advocate for integrating content into YouTube argue that broadcasters shouldn’t view YouTube as a competitor, but rather as what it truly is for them: a simple content distribution platform. YouTube doesn’t own studios, nor does it produce audiovisual content—so it should be seen purely as an additional distribution channel, one that complements the traditional broadcast model.

They go further, explaining that the real competitors for broadcasters are the creators already on the platform (like MrBeast, etc.). Broadcasters should start thinking and acting like these digital creators within the platform—moving beyond the traditional TV channel mindset and evolving toward a production model similar to that of digital creators.

This point hasn’t gone unnoticed by other “relatively new” streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon, which is why they’re trying to attract shows, episodes, and other content from these digital creators to their own platforms.

Building on the previous point, opponents emphasize again that by integrating their premium content, broadcasters are essentially handing over their greatest asset—content—to their competitors.

They explain, for example, that if a broadcaster has a specific advertising budget or investment within a country, taking the step to integrate content into YouTube could risk that the advertiser or media agency decides to allocate that budget through the YouTube platform instead of directly with the broadcaster.

As a result, broadcasters who once had strong commercial leverage in their home markets would end up sharing revenues that were exclusively theirs.

So, as we mentioned, both strategies appear to have solid and valid points, as well as associated risks and threats.

What seems clear is that broadcasters, while making a final decision, should consider integrating only part of their content (not all of it) and avoid integrating their content within the territories or countries where they currently hold strong market power and influence—especially as Big Tech companies continue to increase their market share and dominance.

The ecosystem has changed and will continue to change in many ways in the near future, including:

While from the outside all claims, strategies, and advice may seem valid and optimal, media companies are dealing with a crisis that forces them to focus on the short term and prevents them from fully evaluating long-term strategies—strategies which are often the most effective.

But this is not a decision they can make on their own. At the end of the year, there are investors to answer to, and in today’s world, where only “growth and growth YoY” is demanded, long-term strategies seem to have no place or acceptance.

We all remember and understand the impact that the rise of the Internet had on media— especially the big press media in those years—once the Internet became established. Then it was radio’s turn to experience this shift, and now the time has come for this change to knock on the doors of TV media.

Traditional broadcasters and TV media have long enjoyed a position of power and privilege in their home markets, but today the balance has begun to tip against them. This is a challenge that does not seem to have an easy solution, nor does the trend appear easy to reverse.

We need to look at everything with perspective and understand the uneven battle that traditional broadcasters and TV media face today. Competing against the major global streaming platforms, Big Tech companies, and others—with their vastly superior budgets, revenues, and audiences—feels like an uneven fight.

Perhaps it is time for major pan-regional alliances, and here Europe should be the region making the greatest efforts to try to maintain the situation—not necessarily TV media dominance, but at least a certain balance between US platforms and their independent local media.

We hope to be wrong, but everything seems to lead to the same fate for audiovisual media that historically have had a very consolidated and secure niche in TV—and now, with the arrival of the Internet to this television environment, it could mean the same end that it brought to Media before.

At tvads we has a professional team able to advise you on this field and and guide you in any area of your streaming advertising business, advising you or even operating it on your behalf if necessary

All author posts